ON JUNE 7, 2011, a local businessman addressed a meeting of the Cupertino City Council. He had not been on the agenda, but his presence wasn’t a total surprise. Earlier in the year, the man had expressed his intention to attend a meeting in order to propose a new series of buildings along the city’s northern border, but he hadn’t felt up to it at the time. He was, as all of them knew, in dire health.

Before the start of the meeting, Kris Wang, a Cupertino councilmember, looked out the window at the back of the room and saw him walking toward the building. He moved with obvious difficulty, wearing the same outfit he had been seen in the day before when he’d introduced new products to the world—which is to say, the same outfit that anyone had ever seen him wear. When it was his turn to address the council, he walked to the podium. He began to speak, tentative at first before clicking into the conversational yet hypnotically compelling tone he used in keynotes.

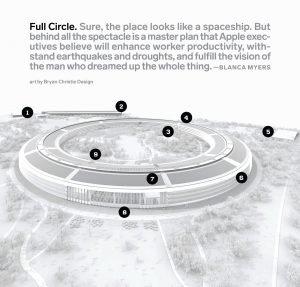

His company, he said, had “grown like a weed.” His workforce had increased significantly over a decade, coming to fill more than 100 buildings as workers created one blockbuster product after another. To consolidate his employees, he wanted to create a new campus, a verdant landscape where the border between nature and building would be blurred. Unlike other corporate campuses, which he found “pretty boring,” this would feature as its centrepiece a master structure, shaped like a circle, that would hold 12,000 employees. “It’s a pretty amazing building,” he told them. “It’s a little like a spaceship landed.”

When Wang asked what benefit would come to Cupertino from this massive enterprise, the speaker had a slight edge to his voice as he explained, as if to a child, that it would enable the company to stay in the California township. Otherwise, it could sell off its current properties and take its people with it, maybe to someplace nearby, like Mountain View. That unpleasantness out of the way, the speaker was able to return to the subject of what he would create.

“I think we do have a shot,” he told the council, “of building the best office building in the world.” What he didn’t tell them—during what none of them could have known would be his last public appearance—is that he was not just planning a new campus for the company he cofounded, built, left, returned to, and ultimately saved from extinction. Through this new headquarters, Steve Jobs was planning the future of Apple itself—a future beyond him and, ultimately, beyond any of us.

ON A CRISP and clear March day, more than five years after Jobs’ death, I’m seated next to Jonathan Ive in the back of a Jeep Wrangler as we prepare to tour the nearly completed Apple Park, the name recently bestowed on the campus that Jobs pitched to the Cupertino City Council in 2011. At 50, Apple’s design chieftain still looks like the rugby player he once was, and he remains, despite fame, fortune, and a knighthood, the same soft-spoken Brit I met almost 20 years ago. We are both wearing white hard hats with a silver Apple logo above the brim; Ive’s is personalised with “Jony” underneath the iconic symbol. Dan Whisenhunt, the company’s head of facilities and a de facto manager of the project, comes with us. He too has a personalised hat. It is an active construction site on a tight deadline—the first occupants are supposedly moving in within 30 days of my visit, with 500 new employees arriving every week thereafter—and I felt a bit like one of the passengers on the first ride into Jurassic Park.

We drive up North Tantau Avenue, past the buildings that will house employees not fortunate enough to sit in the campus’s main headquarters, as well as the half-finished visitor’s centre. Only a few years ago, most of the space was a flat parking lot, but today huge berms—artificial hills—hug the road, blocking views of busy Wolfe Road and Interstate 280 and forming a rolling landscape with hundreds of trees, their roots half-buried in wooden boxes, ready for planting. We drive around campus and turn into the entrance of a tunnel that will take us to the Ring.

Of course, I’ve seen images of it, architectural equivalents of movie trailers for a much-awaited blockbuster. From the day Jobs presented to the Cupertino City Council, digital renderings of the Ring, as Apple calls the main building, have circulated widely. As construction progressed, enterprising drone pilots began flying their aircraft overhead, capturing aerial views in slickly edited YouTube videos accompanied by New Agey soundtracks. Amid all the fanboy anticipation, though, Apple has also taken some knocks for the scale and scope of the thing. Investors urging Apple to kick back more of its bounty to shareholders have questioned whether the reported $5 billion in construction costs should have gone into their own pockets instead of a workplace striving for history. And the campus’s opening comes at a point when, despite stellar earnings results, Apple has not launched a breakout product since Jobs’ death. Apple executives want us to know how cool its new campus is—that’s why they invited me. But this has also led some people to sniff that too much of its mojo has been devoted to giant glass panels, custom-built door handles, and a 100,000-square-foot fitness and wellness center complete with a two-story yoga room covered in stone, from just the right quarry in Kansas, that’s been carefully distressed, like a pair of jeans, to make it look like the stone at Jobs’ favorite hotel in Yosemite.

Inside the 755-foot tunnel, the white tiles along the wall gleam like a recently installed high-end bathroom; it’s what the Lincoln Tunnel must have looked like the day it opened before the first smudge of soot sullied its walls. And as we emerge into the light, the Ring comes into view. As the Jeep orbits it, the sun glistens off the building’s curved glass surface. The “canopies”—white fins that protrude from the glass at every floor—give it an exotic, retro-future feel, evoking illustrations from science fiction pulp magazines of the 1950s. Along the inner border of the Ring, there is a walkway where one can stroll the three-quarter-mile perimeter of the building unimpeded. It’s a statement of openness, of free movement, that one might not have associated with Apple. And that’s part of the point.

Since 1997, Jonathan Ive has overseen the design of every Appleproduct—including the company’s new headquarters.

We drive through an entrance that takes us under the building and into the courtyard before driving back out again. Since it’s a ring, of course, there is no main lobby but rather nine entrances. Ive opts to take me in through the café, a massive atrium-like space ascending the entire four stories of the building. Once it’s complete, it will hold as many as 4,000 people at once, split between the vast ground floor and the balcony dining areas. Along with its exterior wall, the café has two massive glass doors that can be opened when it’s nice outside, allowing people to dine al fresco.

“This might be a stupid question,” I say. “But why do you need a four-story glass door?”

Ive raises an eyebrow. “Well,” he says. “It depends on how you define the need, doesn’t it?”

We go upstairs, and I take in the view. From planes descending to SFO, and even from drones that buzz the building from a hundred feet above it, the Ring looks like an ominous icon, an expression of corporate power, and a what-the-fuck oddity among the malls, highways, and more mundane office parks of suburban Silicon Valley. But peering out the windows and onto the vast hilly expanse of the courtyard, all of that peels away. It feels … peaceful, even amid the clatter and rumble of construction. It turns out that when you turn a skyscraper on its side, all of its bullying power dissipates into a humble serenity.

For the next two hours, Ive and Whisenhunt walk me through other parts of the building and the grounds. They describe the level of attention devoted to every detail, the willingness to search the earth for the right materials, and the obstacles overcome to achieve perfection, all of which would make sense for an actual Apple consumer product, where production expenses could be amortised over millions of units. But the Ring is a 2.8-million-square-foot one-off, eight years in the making and with a customer base of 12,000. How can anyone justify this spectacular effort?

“It’s frustrating to talk about this building in terms of absurd, large numbers,” Ive says. “It makes for an impressive statistic, but you don’t live in an impressive statistic. While it is a technical marvel to make glass at this scale, that’s not the achievement. The achievement is to make a building where so many people can connect and collaborate and walk and talk.” The value, he argues, is not what went into the building. It’s what will come out.

A RING WAS not what Jobs had in mind when he first started talking about a new campus. Ive thinks it was around 2004 when he and his boss first began discussing a reimagined headquarters. “I think it was in Hyde Park,” he says. “When we used to go to London together, we’d spend a lot of time in these parks. We began talking about a campus where your primary sense was that you were in parkland, with many elements that were almost collegiate—where the connection between what was built and a parkland was immediate, no matter where you were.”

The discussions continued and widened throughout the company, but it wasn’t until 2009 that Apple was ready to actually move on the project. Though vacant land in Cupertino is rare, Apple had purchased 75 acres barely a mile from Infinite Loop, its current headquarters. The company began to seek out the right architectural firm to take on the task, and Jobs came to focus on Norman Foster, a Pritzker Prize winner whose commissions have included the Berlin Reichstag, the Hong Kong airport, and London’s infamous “Gherkin” tower. Jobs called Foster in July 2009 and told him, in Foster’s recollection, that Apple “needed some help.”

Norman Foster, one of Apple Park’s architects, had 250 people working on the project at its height.

Two months later Foster arrived in Cupertino and spent an entire day with Jobs, first at his office at Infinite Loop and later at his home in Palo Alto, and discovered that his new client had a remarkably detailed vision of the glass, steel, stone, and trees that would make up Apple’s new home. As Jobs spoke, Foster furiously sketched in the A4 sketchbook he is never without, creating a “word picture” of what Jobs was envisioning. “His touchstone was the quad at Stanford,” Foster says, referring to the main part of the school’s campus where low-slung academic buildings, arranged around large, leafy outdoor areas and designed with open-air pathways where one can walk along the structures’ edges, offer the sensation of being both inside and out.

Foster soon brought in reinforcements from his London-based firm, Foster + Partners, for the first of many meetings Jobs would have with a growing team of architects. Though he always professed to loathe nostalgia, Jobs based many of his ideas on his favourite features of the Bay Area of his youth. “His briefing was all about California—his idealised California,” says Stefan Behling, a Foster partner who became one of the project leads. The site Apple had bought was an industrial park, largely covered by asphalt, but Jobs envisioned hilly terrain, with sluices of walking paths. He again turned to Stanford for inspiration by evoking the Dish, a popular hiking area near the campus where rolling hills shelter a radio telescope.

The meetings often lasted for five or six hours, consuming a significant amount of time in the last two years of Jobs’ life. He could be scary when he swooped down on a detail he demanded. At one point, Behling recalls, Jobs discussed the walls he had in mind for the offices: “He knew exactly what timber he wanted, but not just ‘I like oak’ or ‘I like maple.’ He knew it had to be quarter-cut. It had to be cut in the winter, ideally in January, to have the least amount of sap and sugar content. We were all sitting there, architects with grey hair, going, ‘Holy shit!’”

As with any Apple product, its shape would be determined by its function. This would be a workplace where people were open to each other and open to nature, and the key to that would be modular sections, known as pods, for work or collaboration. Jobs’ idea was to repeat those pods over and over: pod for office work, the pod for teamwork, pod for socialising, like a piano roll playing a Philip Glass composition. They would be distributed democratically. Not even the CEO would get a suite or a similar incongruity. And while the company has long been notorious for internal secrecy, compartmentalising its projects on a need-to-know basis, Jobs seemed to be proposing a more porous structure where ideas would be more freely shared across common spaces. Not totally open, of course—Ive’s design studio, for instance, would be shrouded by translucent glass—but more open than Infinite Loop.

“At first, we had no idea what Steve was actually talking about with these pods. But he had it all mapped out: space where you could concentrate one minute and then bump into another group of people in the next,” Behling says. “And how many restaurants should we have? One restaurant, a huge one, forcing everyone to get together. You have to be able to bump into each other.” In part Jobs was expanding on a concept that he had developed while helping design the headquarters of another company he ran—Pixar—that nudged collaboration by forcing people to stroll longer than usual to the restrooms. (So involved was Jobs in that project that Pixar-ites call the building “Steve’s Movie.”) In this new project, Jobs was balancing an engineer’s need for intense concentration with the brainstorming that unearths innovation.

To accommodate the pods, the main building took the shape of a bloated clover leaf—people at Apple called it the propeller—with three lobes doing a Möbius around a centre core. But over time Jobs realised that it wouldn’t work. “We have a crisis,” he told the architects early in the spring of 2010. “I think it is too tight on the inside and too wide on the outside.” This launched weeks of overtime among Foster’s 100-person team to figure out how to resolve the problem. (Their ranks would eventually reach 250.) In May, as he was sketching in his book, Foster wrote down a statement: “On the way to a circle.”

According to Walter Isaacson’s biography of Jobs, there was another factor. When Jobs showed a drawing of the clover leaf to his son, Reed, the teenager commented that from the air, the building would look like male genitalia. The next day Jobs repeated the observation to the architects, warning them that from that point on, “you’re never going to be able to erase that vision from your mind.” (Foster and Behling say they have no recollection of this.)

By June 2010 it was a circle. No one takes full credit for the shape; all seem to feel it was inevitable all along. “Steve dug it right away,” Foster says.

By that fall Whisenhunt had heard that a former HP campus in Cupertino might be available. The 100-acre plot was just north of Apple’s planned site. What’s more, it had deep meaning for Jobs. As a young teen, he had talked his way into a summer job at HP, just at the time when its founders—Jobs’ heroes—were walking that site and envisioning an office park cluster for their computer systems division. Now HP was contracting and no longer needed the space. Whisenhunt worked a deal, and Apple’s project suddenly grew to 175 acres.

“Steve’s original intention was to sort of blur that line between the inside and outside,” says Lisa Jackson, Apple’s environment czar. “It sort of wakes up your senses.”

Jobs had always insisted that most of the site be covered with trees; he even took the step of finding the perfect tree expert to create his corporate Arden. He loved the foliage at the Dish and found one of the arborists responsible. David Muffly, a cheerful, bearded fellow with a Lebowski-ish demeanor, was in a client’s backyard in Menlo Park when he got the call to come to Jobs’ office to talk trees. He was massively impressed with the Apple CEO’s taste and knowledge. “He had a better sense than most arborists,” Muffly says. “He could tell visually which trees looked like they had good structure.” Jobs was adamant that the new campus house indigenous flora, and in particular he wanted fruit trees from the orchards he remembered from growing up in Northern California.

Apple will ultimately plant almost 9,000 trees. Muffly was told that the landscape should be future proof and that he should choose drought-tolerant varieties so his mini forest and meadows could survive a climate crisis. (As part of its ecological efforts to prevent such a crisis, Apple claims, its buildings will run solely on sustainable energy, most of it from solar arrays on the roofs.) Jobs’ aims were not just aesthetic. He did his best thinking during walks and was especially inspired by rambling in nature, so he envisioned how Apple workers would do that too. “Can you imagine doing your work in a national park?” says Tim Cook, who succeeded Jobs as CEO in 2011. “When I really need to think about something I’m struggling with, I get out in nature. We can do that now! It won’t feel like Silicon Valley at all.”

Cook recalls the last time he discussed the campus with his boss and friend in the fall of 2011. “It was actually the last time I spoke to him, the Friday before he passed away,” Cook says. “We were watching a movie, Remember the Titans. I loved it, but I was so surprised he liked that movie. I remember talking to him about the site then. It was something that gave him energy. I was joking with him that we were all worried about some things being difficult, but we were missing the most important one, the biggest challenge of all.”

Which was?

“Deciding which employees are going to sit in the main building” and which would have to work in the outer buildings. “And he just got a big laugh out of it.”

To read the full article go to Wired.

Written by: Steven Levy

Interesting Links:

Here’s Everything Apple Announced on Tuesday

What to Expect From Google’s Biggest Event of The Year